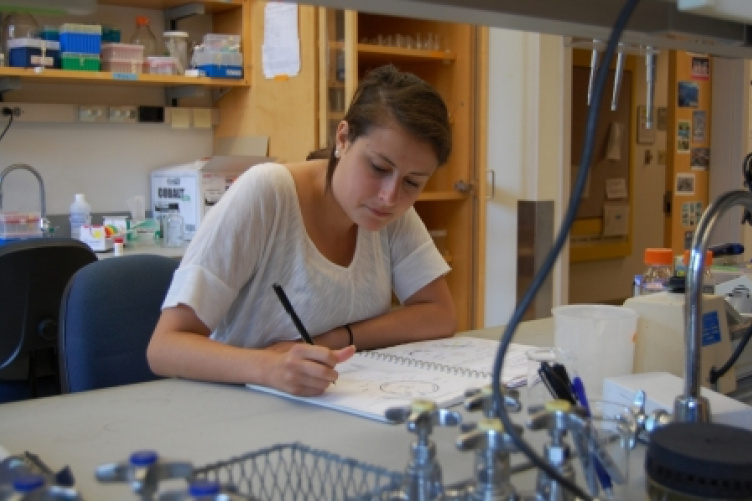

Laura Van Beaver makes notes about her research on how to engineer a better cup of decaffeinated tea.

Tea drinkers will tell you it can be hard to find a really good decaffeinated tea. It’s not the tea sellers’ fault; the process of removing caffeine weakens the taste.

Laura Van Beaver ’16 is trying to change that. A neuroscience and behavior major, Van Beaver spent the summer in the lab of Subhash Minocha, professor of plant biology and genetics, trying to develop a new process for removing caffeine from tea while retaining its health benefits and flavor. Her work was supported by a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) from UNH’s Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research.

The project was started by a visiting scientist from India and then furthered along in early stages by two undergraduate students.

Green and black teas are made from the leaves and buds of the Camellia sinensis plant; the only difference between them is how they are processed. Black tea undergoes more oxidation than its green counterpart. Both contain caffeine. According to the Mayo Clinic, green tea has about 24-45 milligrams of caffeine per cup while black tea ranges from 14-70 milligrams, depending on the length of brewing times. Federal regulations specify that for a tea to be labeled decaffeinated it can’t contain more than 2.5 percent caffeine.

There are four common methods used to remove caffeine from tea: methylene chloride, ethyl acetate, liquefied carbon dioxide, or water processing. Ethyl acetate is used most often in the U.S. The problem is, all the methods tax the antioxidants and impact flavor. What’s more, some people believe the chemicals used to create a decaffeinated tea are more harmful than the caffeine.

“My decaf tea would be dramatically lower in caffeine and preserve the health benefits,” Van Beaver says. “Through genetic modification, a tea product can be produced that maintains its antioxidant properties but is free of, or low in, caffeine.”

The Massachusetts resident’s proposal calls for modifying the synthesis of the caffeine in the tea plant by essentially turning off caffeine production, creating a naturally decaffeinated product. To do that, she is trying to alter the existing gene.

“I think people get nervous when they hear genetic engineering because there has been so much manipulation. But I am not inserting any foreign genes into the plant. Instead, I’m taking a preexisting gene and altering its orientation. It's more natural than other modifications,” Van Beaver says.

Plant breeders have used genetic modification for years to produce heartier crops. Engineering tea, Van Beaver hypothesizes, will lead to a more naturally decaffeinated product that retains the antioxidants people want for better health.

According to Van Beaver, Japanese researchers have used genetic modification to produce coffee that contains 70 percent less caffeine through a technique known as gene silencing or antisense RNA that inhibits the production of caffeine. The practice also can be used in tea leaves, she says.

“Laura showed the excitement that a person definitely needs to spend his or her precious hours in the lab doing what could be described as the most boring tasks of ‘moving solutions around,’” Minocha says. “It matters not if she has this tea plant before graduation or not; she will have added a link in the process that may take a few more undergraduate students to accomplish. And, she, like several others from our lab, is headed to medical school, and what she learns in this research will be handy to face the real life of scientific researchers."

Van Beaver will continue her research during the academic year.

“I am still in the process of engineering a plasmid with the gene in the antisense orientation, and I am germinating tea seeds for use in tissue culture. I hope to finish the project as part of my senior honors thesis, and I am going to continue to work on it next semester. I’ve learned that science is pretty slow.”

-

Written By:

Jody Record ’95 | Communications and Public Affairs | jody.record@unh.edu