Spring is the season of horseshoe crab love, when thousands of females come up on beaches at high tide to spawn, and the smaller males hitch a ride on their backs or scuttle behind them to fertilize their eggs.

Spring is also the season of the horseshoe crab harvest, when fishermen working for biomedical companies pluck them from beaches and take them to labs to extract their precious blue blood. It's the only known source of a clotting agent--Limulus amoebocyte lysate—that's used to test vaccines and medical devices for bacterial contamination. After removing 30 to 40 percent of each animal's blood, the labs put the crabs back in the water or sell them as bait.

New research from UNH and Plymouth State suggests that biomedical bleeding of horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus) might be playing a larger role in their decline than previously thought. The primitive, odd-looking horseshoes play a vital role in coastal ecosystems from the Gulf of Mexico to the North Atlantic, plowing the muck in bays and estuaries to bring up buried nutrients that feed countless other creatures. Their eggs are also a major refueling food for red knots and other seabirds that fly from South America to the Arctic Circle each spring. And while the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) limits the number of horseshoe crabs than can be killed for bait in the eel and conch fisheries, it does not regulate the biomedical harvest, though it does suggest "best practices."

Biomedical companies harvested 530,000 live horseshoe crabs in 2012, according to data gathered by the ASMFC. The companies prefer females because they are bigger and have more blood. Marin Hawk, the ASMFC's horseshoe crab coordinator, says that reports indicate that fewer than 5 percent of the crabs die during extraction and transportation. But no one really knows how the live ones fare after release.

That was the question the team led by Win Watson, UNH professor of zoology, and Christopher Chabot, PSU professor of biology, tried to answer.

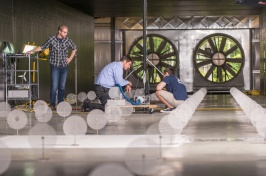

The team captured 56 horseshoe crabs in Great Bay and divided them among outdoor tanks at UNH's Jackson Estuarine Lab and indoor tanks at PSU. For two weeks, the scientists monitored the crabs' movements using tiny accelerometers duct-taped to their backs, video observation, or running wheels (like underwater hamster wheels). Then they mimicked the conditions of industry transport, pulling half the crabs out of the water, placing them in barrels in the sun as if they were on a boat deck, trucking them around for a couple of hours, and—after removing 20 to 30 percent of their blood—reversing those steps.

The results were alarming. Of the crabs that had been bled, 18 percent died. And two weeks after returning to their tanks, the surviving crabs were much less active; their internal tidal clocks—which tell them when to spawn, as well as when to come up on mudflats to eat and when to return to deeper water so they won't get stranded—were disrupted; and they suffered low levels of hemocyanin, a blood protein that carries oxygen throughout their bodies.

"They might not die right away, but they may die prematurely, they may behave abnormally, or they may not mate that year," Watson says.

Although horseshoe crabs can survive without oxygen, being out of water for 24 to 48 hours is debilitating, as is exposure to heat -stresses that can be avoided by transporting them in tanks of cold, well-oxygenated seawater, Watson says. He says regulators should consider enforcing such "best practices," as well as banning all harvesting during spawning season and limiting the number of females the industry can take. He also thinks the biomedical companies should be required to fund independent research on the impact of their industry.

"What you really want is for the people who are making all the money to help figure out how to do this in a more sustainable manner, the same way that some of the money from fishing licenses goes into research about fish," he says.

Originally published by:

UNH Magazine, Spring 2014 Issue

-

Written By:

Katharine Webster | freelance writer