To illustrate the central principle of automotive user interfaces, his area of research, Andrew Kun reaches into his pocket.

“This,” says the UNH professor, tapping his iPhone. “It’s great, and we’ve all gotten used to carrying our whole office with us. But we shouldn’t be using them when we’re driving.”

As our dashboards and front seats accumulate more and more technology, Kun and his team are exploring ways to design these devices to minimize driver distraction while maximizing their service, whether finding a new radio station or directing us to our destination. Although Kun is an engineer, an associate professor in the department of electrical and computer engineering, this research sits at the unlikely intersection of technology and cognitive psychology.

|

|

Indeed, last week psychologists mingled with electrical engineers, computer scientists, highway officials, and at least one insurance company executive at the Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, or Automotive UI, conference, hosted by UNH. More than 170 participants from around the world attended the three-day conference, based in Portsmouth with a field trip to Kun’s Morse Hall lab.

“This conference is about what’s going on in the car with the driver,” Kun says. “How do you interact with devices so your driving is not impacted?”

Kun’s research has its roots in Project 54, the groundbreaking project he led that aimed to decrease distractions in police cruisers with voice-activated commands. The work has taken a civilian turn in the past few years, probing the way we use technology that draws our attention from the road ahead.

And while cell phones and texting have hogged the distracted driving spotlight, they’re hardly the only culprits. Personal navigation devices (industry speak for in-vehicle GPS systems), radios, video calling (spoiler: it’s distracting), and even conversations with passengers all have an effect on our attention to driving. Kun and his team of colleagues, graduate students, and undergraduates want to better understand that effect.

Watch the driving simulator in action as Kun and colleagues test various navigational devices.

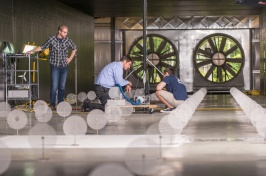

Much of what they’re learning happens via his lab’s driving simulator. A sort of video-game-on-steroids, the simulator comprises a highly realistic driver’s cab of a car fully instrumented to measure eye movement, pupil dilation, and other cognitive activity. It’s surrounded on three sides by a screen on which the road and surroundings are projected, making for a highly engaging driving experience.

With conference participants behind the wheel of the simulator last Wednesday evening, research engineer Oskar Palinko demonstrated the team’s work on personal navigation devices. “We’re looking at different kinds of GPS solutions that might be better than what we have,” he says. In one study, they found that GPS devices with map displays, the majority currently in use, caused drivers to look away from the road much more than those with spoken directions only. Nonetheless, drivers express a strong preference toward looking at the maps.

Ph.D. student Zeljko Medenica, along with Kun, affiliate associate professor Tim Paek, and Palinko, have tested an emerging navigational technology that uses augmented reality. Known as a heads-up display, these GPS devices display navigational directions – arrows or a “virtual cable” (www.mvs.net) to follow -- directly onto the windshield, so the driver does not need to glance away from the road. And ECE undergraduate students Tina Tomaszewski, Meredith Swanson, Zachary Cook, Adam Downey, and Aaron Lecomte are creating and testing an LED display on the dashboard, just above the steering wheel, that will direct drivers. “Instead of having to look down at your GPS, you can stay focused on the road,” says Cook of their lower-cost solution.

As electrical engineers like Kun cross the disciplinary divide to integrate how humans experience the technology they create, a conference like Automotive UI provides a welcome sounding board for this emerging field. “I can hear ideas and other views and bounce things off colleagues,” he says, adding that the mix of participants from academia, government and industry proves especially fruitful. “This is a conference where you can think about a new idea, put some research forward, and in the end this is research you can put into cars.”

And while chairing the conference kept Kun and his UNH colleagues very busy, he acknowledges that it was an honor. “It’s a measure of our success that this premiere conference for automotive user interface is hosted by UNH and the department of electrical and computer engineering,” he says.

Read more about the Automotive UI conference and about Kun’s research here.

Originally published by:

UNH Today